The best way to weather a drought is to be ready when it comes.

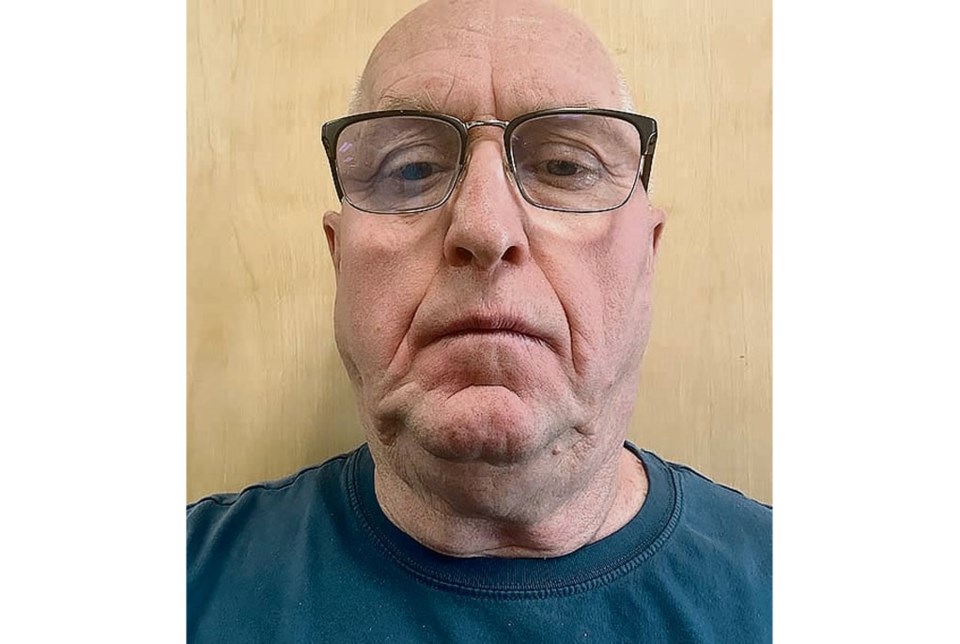

Preparation is needed before the rains stop, says Joe Harrington, irrigation specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation.

“Over the years, I’ve been through several of these dry cycles. We’ve had a funding program since the drought of 2001,” he said during a Foothills Forage webinar.

A call centre was created at the same time, and “every time it gets dry like this, the calls go up dramatically,” said Harrington, who works out of Lethbridge. “It’s just a sign that the industry is not that good at getting ready for the next drought.”

Farmers who are digging dugouts now may not be able to fill them this year, he said, and even if a lot of rain falls, water supplies should be secured.

“It’s also about making money and efficient use of your resources. Using this water resource efficiently really is super critical,” said Harrington.

Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation has a template to help farmers document their long-term water plan, a crucial step in understanding shortcomings.

“Most of you, I’m sure you have a plan, but it’s just in your head,” he told those on the webinar. “Honestly, formalizing it can point out some of the deficiencies in your planning.”

When the plan is written, family or hired helpers will know how to follow it.

“Then as you change your farm, you’ve got a base to work from,” said Harrington.

A long-term water management plan can be used to calculate how much water is needed for each livestock use.

“You probably have many paddocks, and each one requires water. Do you have it in the right place? And what can you do to have water in that place? Do you have to construct another dugout? Do you have to drill another well or can you move water via pipeline?”

The main water sources are surface water, ground water and pipelines. Producers can also use storage tanks, haul water or use temporary pumps. Water wells are the most common source.

“Water wells are very reliable, even in dry conditions,” Harrington said. “They don’t vary a lot with the surface conditions, so in dry conditions, it takes quite a few years for the aquifers to drop in capacity.”

Water wells also have less chance of contamination.

Dugouts are the next most common water source and are dependent on current conditions and those of the year before. They are susceptible to contamination and water quality can be affected.

“Water wells are more popular for a reason,” Harrington said. “They sometimes cost a little more than dugouts, but dugouts over the long run can probably cost almost as much as water wells.”

When it comes to pipelines, Harrington endorsed shallow buried lines that are plowed in. Some producers are reluctant to do that due to cost but pipelines can be a cheaper way to move water. He recommends using black poly pipe and has seen 1.5-inch pipelines that run over two miles.

Volume may be limited, but if there is a large tank or trough at the other end, it can be viable. Pipelines can also freeze with water inside without problems, said Harrington.

Water co-ops are an option in some areas. Farmers sometimes balk at the cost of membership, but it can be cheaper than digging a well.

Harrington encouraged people to identify current water supplies, their reliability and determine whether they have legal access to the water they want to use.

The Water Act falls under Alberta Environment and Protected Areas. The current act was developed in 1999 and has not changed a lot since. Water is technically owned by the Crown. Every human has a right to water, and it belongs to everyone.

The Water Act secures certain rights and access to all Albertans, including those in agriculture. It can be divvied out through the water licensing process, which is how people obtain water rights.

Household use is identified as the most important category under the act.

“Under the Water Act, you have the right to access 275,000 gallons per year and you can do that without any licensing,” said Harrington. “You can apply for a water licence to divert a specified amount of water based on what you are using it for.”

There are no new licences available in the South Saskatchewan river basin. There are still exemptions for traditional agriculture use, such as using water from a dugout that is under 550,000 gallons. No licence is required to divert water from a creek or a slough if the land around it is traditionally grazed.

“The licence gives you rights to use a specified amount of water, with specific uses, and provides a right to access based on the date of application,” he said. “The licence is the ability to use the water, but if you need to construct something, you’ll need approval.”

However, there are some exemptions to this, such as building one dugout per quarter.

Alberta Environment and Parks has regulatory information along with an online application for a licence or for project approval. Water specialists in Alberta can be reached by calling 310-FARM.

Related

Calgary Cargill Case Ready workers overwhelmingly endorse strike

Workers at Cargill’s Case Ready Plant in Calgary have unanimously voted in favour of strike action