The Saskatchewan River Delta, its English name, is the largest freshwater river delta in North America. It stretches from the area around Cumberland House Cree Nation to Cedar Lake in Manitoba and is home to generations of Cree and Métis families.

As his son pilot the airboat down its banks, Carriere sees decay.

Walls of phragmites — an invasive tall grass — choke native species on the banks. The river cuts narrower and deeper than it did when he was a child 50 years ago. Its small tributaries are starving. Fewer animals dart along the wetland.

He was a boy during the construction of the E.B. Campbell and Gardiner dams along the South Saskatchewan River in the 1960s. Now 62, he sees how water flows in the Delta have changed amid a transformation that may threaten its ecological and cultural significance.

The dams reduce water flow to the Delta and block silt, transforming it from an expansive wetland to a potentially deep, unproductive channel. And the Saskatchewan government's $4-billion irrigation project at Lake Diefenbaker announced last year might further affect its health.

The need for a solution is mounting as the Saskatchewan River Delta undergoes a decades-long deterioration impacting local culture and language and vital species of wildlife ranging from moose and black bears to millions of waterfowl and migratory birds. The 10,000 square kilometre Delta's peatland and boreal forests similarly store billions of tonnes of carbon.

It's all concerning for Carriere, who was in Saskatoon for cancer treatment earlier this past summer. When he looked at the South Saskatchewan River winding its way north from a hospital parking lot, he saw a warning for his home. He wondered if the Delta would lose its vitality, coming to resemble Saskatoon's river.

"The province and the country definitely don't know what's going on. The local people have a better idea. We see it every day. As the water shrinks, everything else will shrink with it," Carriere said.

Changing water flow

Carriere grew up on the trapline. He received a dozen traps when he turned 12 and became a commercial fisherman shortly after he finished school by Grade 9. But childhood memories of muskrat and other animals teeming the banks are growing more distant.

In one case, the average moose population in the Delta from 1985 to 2015 was 3,678. That number was as low as 2,553 in 2015, according to a 2019 study published in the scientific journal Alces. Researchers attributed this to "hydroelectric development altering delta ecology and allowing increased human and predator access, and vegetation succession."

Each year since the dams went up, Carriere has seen fewer animals and fish.

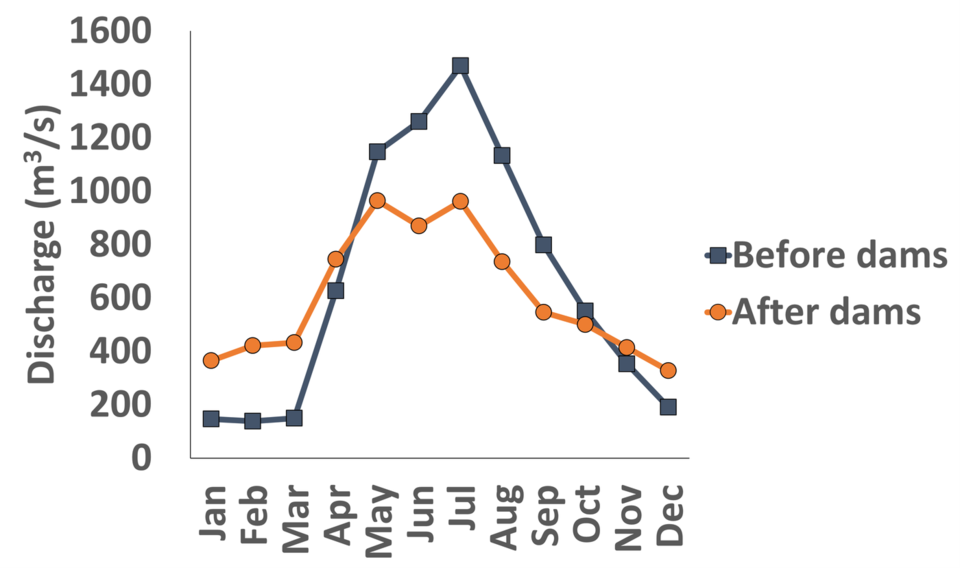

When power demand in Saskatchewan is high during the winter, the dams release unnaturally high amounts of water to generate it. Water flow is much lower in the spring and summer, explains University of Saskatchewan Professor Tim Jardine.

With less water in the summer, less goes into wetlands. Those pulsing releases lead fish into shallows where they are trapped when the water falls back, he said.

Dams also trap sediment-like silt. Without the sediment, "the river is hungry," University of Saskatchewan socio-hydrologist Graham Strickert said. It pulls sediment from the banks and the riverbed to replace what's trapped. As it does, the river gets deeper and can't flow into the channels branching off it. The wetlands bordering the water stagnate.

If nothing changes, Strickert predicts the Delta will eventually look like the South Saskatchewan River cutting through Saskatoon: a long, deep single unproductive channel that rarely floods. Whether that comes to pass is vital because the health of the culture and language dialect referred to as Swampy Cree is entwined with the Delta.

“It’s saddening, of course. There’s a lot of wildlife that depends on this place and until two years ago, nobody on the government level seemed to care,” Strickert said, referring to when SaskPower began communicating directly and regularly with downstream stakeholders.

He also pointed to a recent Delta visit by cabinet ministers and agency heads and collaborative efforts to understand the situation to pursue active stewardship and restoration activities.

Joel Cherry, a spokesman for SaskPower, wrote in a prepared statement that the Crown corporation “recognizes that issues, concerns and challenges in the Saskatchewan River Delta are complex and that E.B. Campbell is only one aspect among many that influence environmental conditions in the Delta region.”

The Crown service’s overall vision is to proactively manage environmental risk, limit the impact and push for a net-neutral impact, backed by transparency and collaboration and both traditional knowledge use and scientific data collection, he said.

Water Security Agency spokesman Patrick Boyle said work on the provincial irrigation project at Lake Diefenbaker has involved consultation with Friends of the Delta and Cumberland House leadership.

Flows are consistently monitored from Gardiner Dam and adjustments are made to maintain minimum flows, he said.

"We know that there's water available for irrigation, and that was the original intent of Lake Diefenbaker, more work will be done as the project is still in the very early stages,” he said.

Bridging Indigenous and western knowledge

Gary Carriere hopes bridging traditional knowledge and western science can educate the government of the Delta's peril and slow its demise.

A recent push for Indigenous-led conservation of the Delta may be a step toward this. In June, Cumberland House Cree Nation Chief Rene Chaboyer affirmed its sovereignty over the Delta, pushing for greater environmental and economic controls of the region.

Solomon Carrière was born and raised in that territory. He and his partner Renée have lived about 50 kilometres north of Cumberland House for the 40 years of their marriage. Their camp is filled with mementos of Solomon's time as a champion paddler, dotted with guest cabins and running dogs.

Renée worries as she watches the water ebb to reveal several yards of sandy beach that was never there before.

“Yes, (the river's) hungry. But not naturally. The dam is making it hungry,” said Solomon.

“There’s other ways of seeing the world,” Renée said, adding that Indigenous knowledge must become accommodated on a policy level.

"We need it put into action with the creation and implementation of a downstream plan."

Both Indigenous knowledge systems and western science are confident the Delta has changed, noted Razak Abu, a researcher who published a 2019 study about bridging Indigenous knowledge and western science in the Delta.

But science fails to document the processes of social change Cumberland House Cree land users experience, he said.

That's particularly concerning for access to traditional food sources. He thinks governance of the region has to include equally balancing Indigenous and western knowledge.

Abu adds there is no scientific instrument or measurement to determine if the fish or meat in the area is different from previous generations.

"What it shows is that no one knowledge system is able to tell us everything about an event. ... So, then the question is what can one knowledge system tell us that the other knowledge system couldn't tell us."

Costly solutions

Despite changes at the E.B. Campbell Dam in 2018, low water releases in spring and summer continue, and scientists like Strickert point out that the river remains starved of sediment.

With substantial spending on the way for the Lake Diefenbaker irrigation project, it is possible to restore some sediment to the river, so that it ceases to eat into its bed and banks, he said.

Despite an unclear cost, he thinks that needs to be part of the conservation.

But it may very well be prohibitively expensive to move massive amounts of silt and sediment to the Delta, according to Norman Smith, a University of Nebraska geologist who's made the Delta his life's work and is a longtime friend of Gary Carriere.

He doubts saving the landmark is possible and adds the impacts of the Diefenbaker Lake irrigation project are difficult to measure.

Smith is clear: any water pulled from the system is a one-way process. Any drop taken from Lake Diefenbaker won't go to the Delta. That drying of his life's subject will continue; there's nothing more he can say.

"At what point can we say it will only have so many years of life? It'll be very gradual. It'll affect different parts of the Delta at different rates," he said, noting the lower parts may have a longer lifespan.

"It's painful seeing it dry up. It's only going to get worse and worse."

There are some solutions worth investigating to reduce water loss at Lake Diefenbaker, noted Jared Suchan, a Ph.D. candidate for environmental systems engineering at the University of Regina.

Estimates show evaporation is one of the biggest consumers of water at Lake Diefenbaker.

With optimized water application and climate-crop modelling, reduced water use is possible, he said.

Alternatively, pipes and enclosed canals could cut back on evaporating water.

Up to your shoulders

SaskPower participates in Delta Dialogue, a forum coordinated by the University of Saskatchewan that shares information and water and environmental concerns.

Those ties extend to local land users. SaskPower provides annual funding to local fishermen to enable lake sturgeon index fishing, which currently shows a positive trend in the fish population, a spokesman said.

It also funds research projects and recently spent $40,000 and $70,000 in 2020 and 2021, respectively, to clear wood debris in the Delta and open boat and fish passage through side channels.

Those funds have found their way to a small camp in the River Delta, where in late August, a handful of local fishermen armed with overalls and chainsaws hacked at the wood jamming Delta channels and trapping local fish.

Gary Carriere's son, Gary Jr., works with them for days at a time. It's a difficult task. The water can be as high as his chest when he cuts logs, and the soaked wood quickly dulls any saw.

The men he works with have known his father for decades and when the senior Carriere visits, the buzz of the camp rests and the fishermen crack jokes, speaking in Cree and sharing a laugh on the front line of a battle for the Delta's future.

One of those men cracking jokes is Durwin McKenzie.

There was a time when McKenzie would be out moose hunting in the late summer. Now clearing the channel has taken centre stage.

The willows framing the channel were never there when he fished with his father and uncle there 25 years ago, he said. Now, waterways like it are jammed.

“It's impacting our culture because the water levels and log jams are plugging up everything. You can't do what we used to do,” he said.

“Would they have protected it right away?”

Cumberland House Cree Nation band councillor Angus McKenzie, who is a trapper and fisherman, thinks the thousands of dollars going toward channel clearing may be too little too late.

“Sure, come down, meet with us. Help us. But like I said, it will never be the same."

"How do you replenish a Delta this big? Where do you start?"

These challenges aren't new — McKenzie thinks farmers suffering from drought could easily relate to what he’s experiencing on the Delta.

“Our (environment) is being destroyed. And if it ever happened to you, you would feel it,” he said. “If this Delta was further south, would they have protected it right away?”

Another band councillor, Julius Crane, is optimistic, despite the challenges. He's hopeful that restoration can happen, and he thinks partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups can help secure it.

Crane pictures future generations of band members living among flourishing wildlife and fish.

“That’s still possible. It’s never too late,” he said. “This has been our home for time immemorial. It’s going to continue to be our home.”

Flowing water

Chasing revitalization is not just for the Delta, but for an entire province bound together by the thread of water flowing through cities, farmers' fields and First Nations.

That sentiment is written on a sign welcoming visitors to Treaty 5 at E.B. Campbell Dam — reflecting a document that intended to last as long as the rivers flow.

That's not lost on Chief Rene Chaboyer, as he sets his sights on the Delta's survival and the hope of its revitalization.

"We have to find a way, a better flow of water to our Delta," he recently told reporters.

Downstream, Gary Carriere's son pilots the Everglades-style airboat that draws the eyes of visiting tourists and scientists who befriend Carriere when they visit. Those relationships are a case of study of Indigenous knowledge bridging itself with scientific study.

Today, Gary Carriere is spending many of his days in a Saskatoon hospital room battling cancer. Among his health woes, he still presses for the future of the Delta’s drying banks while remaining hopeful.

It's natural to wonder if future generations will share his memories of flocks of birds singing overhead or schools of fish splashing out of the Delta's waters.

The decline is clear to the eye; there are fewer members of those species each year, but Carriere never grows tired of watching the animals that burst with life from the Delta's banks.

"It's probably on its way to die," Carriere says. "My hope would be to prolong the life of it."