YORKTON - Bernie Saunders was a hockey player, which as a Canadian kid in the later 1960s and into the ‘70s was not unusual.

What was different with Saunders was that he is black, and that was something unusual for the time.

As a result, Saunders faced a barrage of racism as he climbed through hockey dreaming of a shot at the NHL.

“When I played in the late ‘70s most arenas I played in nobody had seen a black hockey player before. The racism I faced was unthinkable . . . The racism just weighed down on me,” he said in a recent interview with Yorkton This Week.

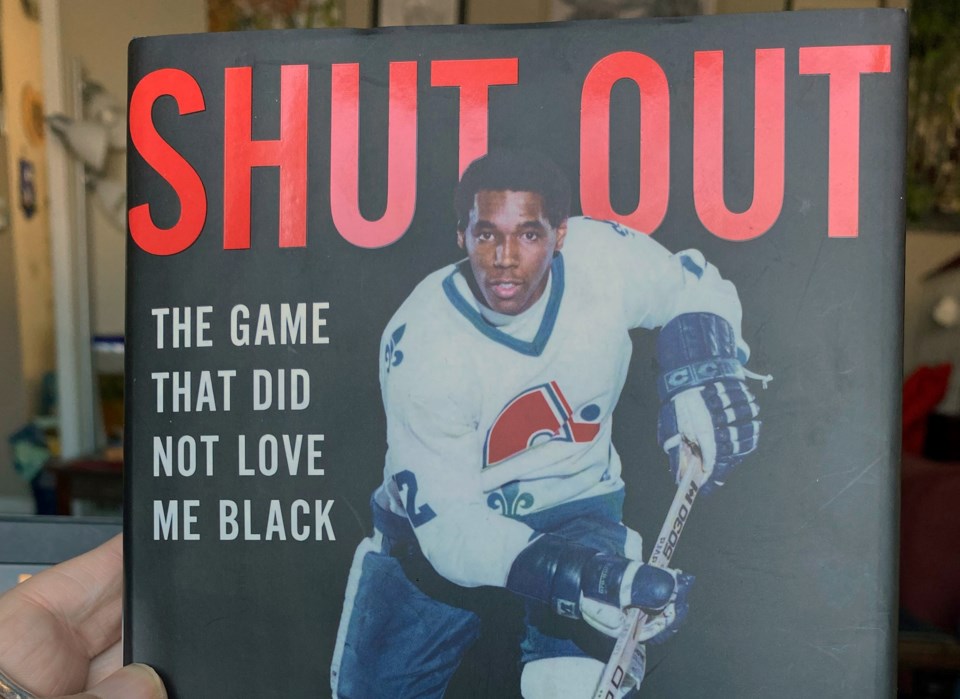

The racism Saunders dealt with, or at least some of it, is chronicled in his recent book; Shut Out: The Game That Didn’t Love Me Black.

Saunders retired from pro hockey in the mid-1980s having a cup of coffee in the NHL – 10 games with Quebec – so the book took decades to see the light of day.

At age 66, Saunders said he still wasn’t sure he should pen the book.

“There was a lot of soul searching. It was an on again, off again project,” he said, adding it was a friend that finally convinced him, but it was still a huge step.

“I’m a very private person,” he said, adding given the years that had passed since he played, and the subject matter he “. . . wasn’t sure how it would be accepted.”

But, ultimately as a 66-year-old black man he felt he had to tell his story in the hopes it might help at least a little in terms of reversing what he sees as a disturbing trend, racism growing.

Saunders said he is seeing the worst racism in 25 years directed at himself and his sons.

“One book isn’t going to change the world,” he said, adding it is just his story in the face of a world seeming to be backsliding on racism.

Saunders said he had thought efforts towards eliminating racism “was on a good trajectory, but the last five, or six years’ things have went dramatically backward. It’s very disappointing.”

And, until every element of racism is eliminated work remains to be done.

“Racism is still racism,” said Saunders, adding that it might have been marginally easier growing up in Canada as a black player because the country is generally more tolerant, he still faced repeated racism “on the ice and off the ice.”

“With me parachuting into their camps out of nowhere, I doubt those coaches could ever conceive of a Black hockey player. That’s one of the many difficulties of racism: it can be a matter of degree. There is a form of implicit bias called implied incompetence. I doubt there was any malice intended, but nobody had ever seen a Black hockey player before. So, even though I already had a year of Junior B under my belt, those coaches likely could not see me as a qualified player,” wrote Saunders.

Saunders said while racism is generally getting worse, in hockey there is talk of being open to all, but he questions whether that is the case.

“Hockey is a conformist sport,” he said, adding players who are willing to fit the mold in how they dress and act may be accepted, but “act like your race, and I’ll use P.K. Subban as an example you’re not going to be accepted.”

The attitude of hockey to be conformist has cost the sport in American markets, suggested Saunders, who noted at one time hockey and basketball were generally equal battling for fans, but basketball has exploded and conformist hockey has lagged behind.

“It’s disappointing, especially having lived in the U.S. and seeing how they left such a huge market on the table,” he said.

But he also reminds in the book he loved the game.

“This is also a love story. Unrequited love, but love nevertheless. Hockey made me and my brother. Although I am happily estranged from the game, I identify to my core as a hockey player,” Saunders wrote.

“Soon after being introduced to the game, I was smitten. Here I was, playing this fun and exciting sport … and doing it with my big brother. We played every chance we could. Back in those days, we didn’t need an artificial ice surface in a controlled environment that charged by the hour. Whether in Toronto or Chateauguay, where we moved when I was 11, I found that kids just hiked to the nearest neighbourhood park and joined the current game of shinny. Outdoor rinks were scattered all around. When the ice became slow or if it snowed, which happened frequently, there wasn’t a lumbering Zamboni trudging out to manicure the ice. No, we all grabbed shovels and refreshed the surface the old fashioned way . . .

“Soccer had been called the beautiful game, but there is nothing that rivals the fast-paced fluidity of a well-played hockey game. From the stands, it can sometimes resemble organized chaos. In reality, it is choreographed improvisation.

“The choreography comes from the coach, who dictates strategy and style. The improvisation comes from the license each player possesses because certain situations arise repeatedly throughout each game. And so, the player master’s specific moves in these predictable conditions gains tremendous advantage.”

But, how had Saunder’s book been accepted?

By the hockey establishment he said it has been largely ignored, with not even a note of congratulations from the NHL which has a department dealing with the issue of discrimination.

“It’s not surprising, but disappointing,” said Saunders. (In hockey) if you say something that doesn’t parallel with its talking points they just ignore you.”

Hockey and sports media didn’t jump on the book at its release either, he noted, adding news media showed greater interest than those dedicated to telling hockey stories.

But Saunders said calls from families and youth facing issues today are gratifying, and make the book worthwhile.

“I’m glad I did it,” he said.

And I’ll leave the last words to Saunders who wrote; “Racism shouldn’t be a “me” problem, it should be a “we” problem.”