THE CONVERSATION — Recently a politician from a village in Prince Edward Island displayed an offensive sign on his property in which he proclaimed there is a “mass grave hoax” regarding the former Indian Residential Schools in Canada. Although many have called for him to resign, he is just one of many people who subscribe to this false theory.

A hoax is an act intended to trick people into believing something that isn’t true. Commentary that a “hoax” exists began circulating in 2021 around the time of public announcements from First Nations across the country that — through the use of ground penetrating radar and other means — the remains of Indigenous children are suspected to be in unmarked graves at or near some former residential schools.

Commentators circulating allegations of a “hoax” contend journalists have misrepresented news of the potential unmarked graves, circulating sensational, attention-grabbing headlines and using the term “mass grave” to do so. They also contend some First Nations, activists or politicians used this language for political gain — to shock and guilt Canadians into caring about Indigenous Peoples and reconciliation.

Like the councillor in P.E.I., many people — in Canada and internationally, fuelled partly by misinformation from the far-right — are accepting and promoting the “mass grave hoax” narrative and casting doubt on the searches for missing children and unmarked burials being undertaken by First Nations across Canada.

There is no media conspiracy

As two settler academic researchers, we decided to investigate the claims of a media conspiracy and fact-check them against evidence.

What did Canadian news outlets actually report after the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation made their public announcements about their search for missing children?

To find out, we analyzed 386 news articles across five Canadian media outlets (CBC, National Post, the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star and The Canadian Press) released between May 27 and Oct. 15, 2021.

What we found, according to our evidence from 2021, is that most mainstream media did not use the terminology “mass graves.” Therefore, we argue that the “mass grave hoax” needs to be understood as residential school denialism.

‘Preliminary findings’ of ‘unmarked burials’

After some public confusion over the specific details of the May 2021 Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announcement, which named “preliminary findings” regarding “the remains of 215 children,” the First Nation clarified the findings as the confirmation of “the likely presence of children, L’Estcwicwéý (the Missing) on the Kamloops Indian Residential School grounds” in “unmarked burials.”

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation had already identified 51 student deaths at the Kamloops school using church and state records.

A National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation Memorial Register has to date confirmed the deaths of more than 4,000 Indigenous children associated with residential schools.

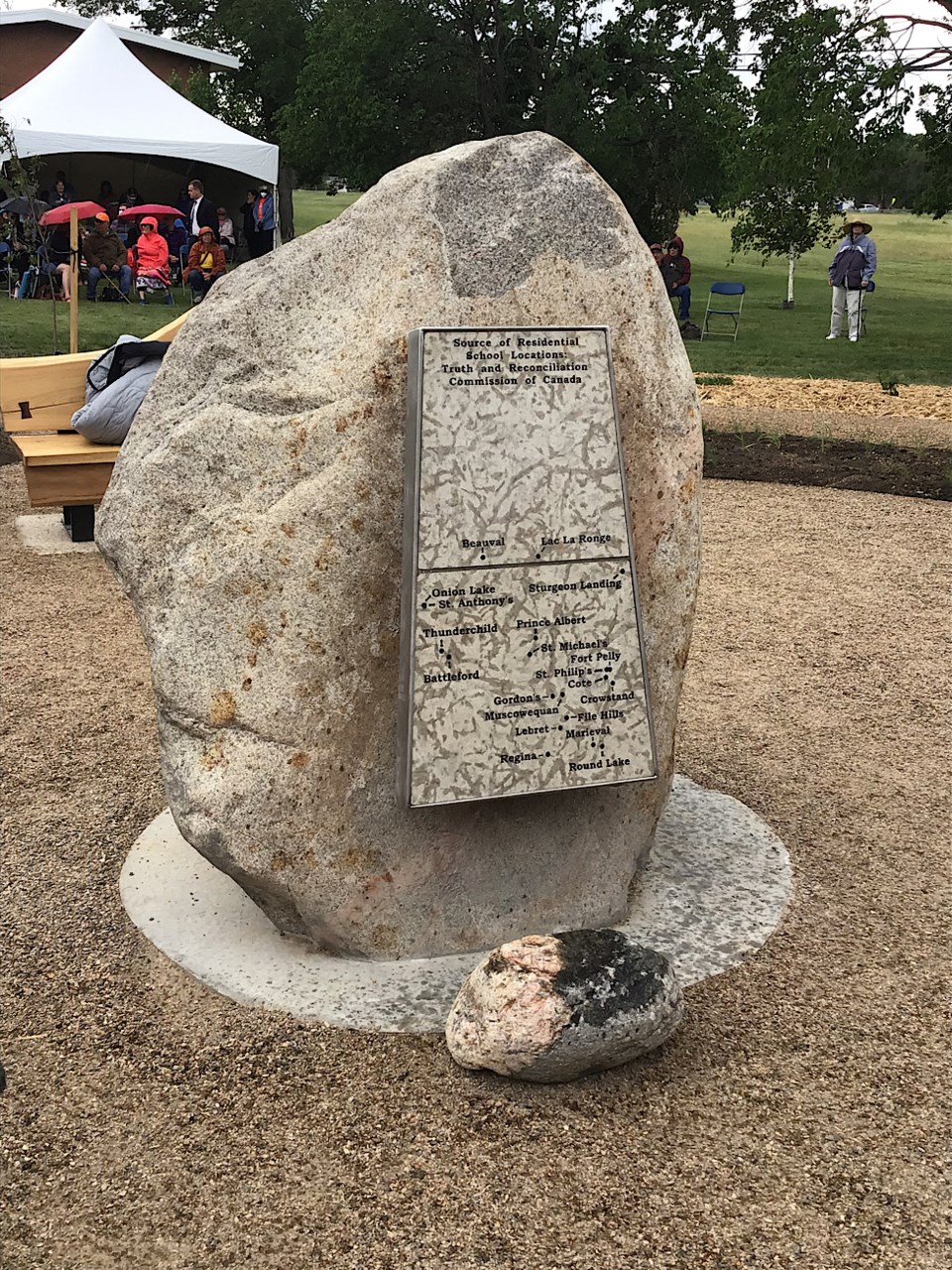

But the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) noted its register of missing children was incomplete, partly due to a large volume of yet-to-be-examined and destroyed records. The TRC’s Calls to Action 71-76 refer to missing children and burials.

The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation — responding to these calls — initiated further research to learn the full truth to facilitate community healing.

Countering harmful misinformation

In the two years since, a number of commentators, priests and politicians, including the P.E.I councillor with his sign, have downplayed the harms of residential schooling — or questioned the validity, gravity and significance of the the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation’s announcement.

One National Post commentator wrote that the account of a “mass grave” was reported “almost universally” adding that this narrative, and subsequent “discoveries” preceded a descent into “shame, guilt and rage …”

Despite the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation’s announcement never mentioning a “mass grave,” and Chief Rosanne Casimir saying in a news conference, “this is not a mass grave, but rather unmarked burial sites that are, to our knowledge, also undocumented,” some have even wrongly suggested the First Nation “announced the discovery of a mass grave” and this was a “fake news story.”

In response, the independent special interlocutor for missing children and unmarked graves and burial sites associated with Indian Residential Schools has amplified calls for Canadians to take responsibility for countering such harmful misinformation.

We hope that our research can contribute to this work and that our report helps to debunk the “mass grave hoax” narrative specifically.

Cherry-picked ‘evidence’

Our report reveals that most Canadian news outlets did not use the language, “mass grave.” The idea that a “mass grave hoax” exists is a myth.

Myths, however, are not pure fiction; they often contain a kernel of truth that is exaggerated or misrepresented.

This selective representation of evidence is commonly referred to as cherry-picking, and it’s easy to see how those spreading the “mass grave hoax” narrative rely on cherry-picked evidence.

Of the 386 articles reviewed in our study, the majority of the articles (65 per cent, or 251) accurately reported on stories related to the location of potential unmarked graves in Canada.

A minority (35 per cent or 135 articles), contained some inaccurate or misleading reporting; however, many of the detected inaccuracies are easily understood as mistakes and most were corrected over time as is common practice in breaking news within the journalism industry.

Of the 386 total articles, only 25 — just 6.5 per cent of total articles — referred to the findings as “mass graves,” with most of the articles appearing in a short window of time and some actually using the term correctly in the hypothetical sense (that mass graves may still be found).

That means that 93.5 per cent of the Canadian articles released in the spring, summer and fall of 2021 that we examined did not report the findings as being “mass graves.”

It appears that some journalists and commentators misunderstood a large number of potential or likely unmarked graves for mass graves in late May/June 2021. By September, denialists were misrepresenting the extent of media errors to push the conspiratorial “mass grave hoax” narrative online.

Our research shows that the “mass grave hoax” narrative hinges on a misrepresentation of how Canadian journalists reported on the identification of potential unmarked graves at former residential school sites in 2021. And we hope our report sparks a national conversation about how important language is when covering this issue.

Media needs to be precise with language and also acknowledge its errors (and avoid future ones), or clarify details in a way that feeds truth, empathy and more accurate reporting — not denialism, hate and conspiracy.

Challenging Residential School denialism

The “mass grave hoax” narrative cannot be reasonably seen as just skepticism. Rather, it should be understood as an expression of residential school denialism.

According to Daniel Heath Justice and Sean Carleton (one of the authors of this story), residential school denialism is not the denial of the residential school system’s existence. Nor do denialists, for the most part, deny that abuses happened.

Residential school denialism, like climate change denialism or science denialism, cherry-picks evidence to fit a conspiratorial counter-narrative. This distorts basic facts and the overall legacy of the Indian Residential School System (IRSS) to alleviate settler guilt and block important truth and reconciliation efforts.

Truth before reconciliation

Our research shows how detailed analysis can be an effective tool in confronting the growing threat of residential school denialism and other kinds of misinformation and disinformation, as called for recently by many Indigenous communities.

Instead of directing ridicule and outrage at denialists — which can give them a larger platform — what is needed is deep and reasoned analysis of their discourse to show why they are wrong or misleading.

This is the strategy of disempowering and discrediting residential school denialism advocated by former TRC Chair Murray Sinclair.

We hope others will join us in this type of research to help Canadians learn how to identify and confront residential school denialism and support meaningful reconciliation.

Our full findings can be read in our new report for the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba.

As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission said in its final report, without truth there can be no genuine reconciliation.

For those who may be experiencing trauma or seeking support, here are some resources:

— The Indian Residential School Survivors Society’s 24/7 Crisis Support line: 1-800-721-0066

— The 24-hour National Indian Residential School Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419

The Conversation used the term “mass graves” in a story published in the days following the announcement by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation. The article has since been updated to use the term “unmarked graves.”![]()

Sean Carleton, Assistant Professor, Departments of History and Indigenous Studies, University of Manitoba and Reid Gerbrandt, MA Student, Department of Sociology and Criminology, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.