REGINA — A Saskatchewan Health Authority business card with a number written on it lay on the ground where Samwel Uko's body was pulled from a lake.

Jurors at a public inquest into his death heard Monday that Uko had placed it there before he drowned himself on the Saskatchewan legislature grounds just over two years ago.

Among the items Uko placed on the ground — a cellphone, wallet, keys, jacket — it was the card that got Daniel Ripplinger's attention.

"It just stuck out in my mind," said the Regina firefighter who helped pull Uko's body out of the water following a 70-minute search.

Earlier that day Uko, who was 20 and originally from Abbotsford, B.C., had sought mental help at the Regina General Hospital.

He was brought to hospital the morning of May 21, 2020, by his cousin, who wasn't allowed to stay due to COVID-19 protocols, the inquest heard.

Uko was discharged a few hours later, but around suppertime he called the Regina Police Service to say he needed help and wanted to go back to the hospital.

The jury heard that police dropped him off at the emergency room, but Uko was eventually removed by security guards.

Two hours later, police and firefighters responded to a drowning call at Wascana Lake. The jury heard there were no drugs or alcohol in Uko's body. He didn't have any external injuries.

Uko's uncle Justin Nyee believes his nephew was turned away because he was Black.

"He did not fit the description of a person who might need help to the people who was there," Nyee, who is from Calgary, said outside the inquest. "They did not feel compassionate about him. They did not treat him as a human. They just discredited him and just threw him out.

"If he was, let's say, someone else, someone would have cared. This is a person sitting there crying, 'I need help.' But they did not, because they did not see him like one of them."

Nyee said he hopes the inquest will provide the family with some long-awaited answers.

"We have so many questions."

John Ash, executive director with the Saskatchewan Health Authority, admits Uko wasn't given the level of care he deserved.

"We failed him," Ash said at the inquest.

The health authority broke its own policy the second time Uko visited the hospital, he said. Staff failed to admit him as an unidentified patient when they couldn't confirm his name.

"Sometimes it's difficult to discern what is a first name or a last name or what is a middle name," Ash said. "This led to confusion amongst the registration clerk."

The health authority has since changed its policy to say people — identified or not — must see a doctor first before getting discharged or removed from hospital.

Uko's parents, Joice Guya Issa Bankando and Taban Uko, flew in from Vancouver to attend the weeklong inquest.

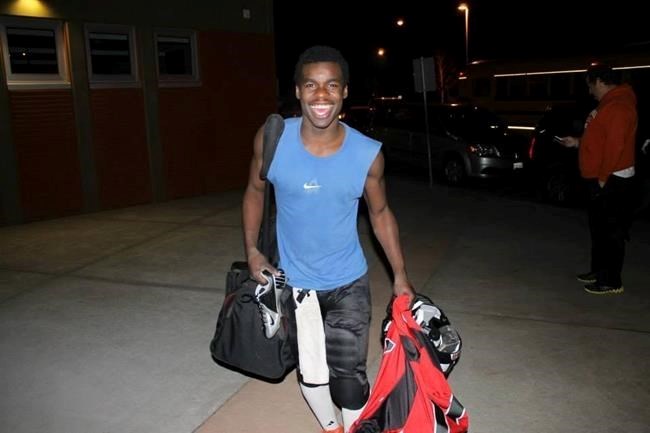

His mother gripped a framed photo of her son smiling and wearing a football jersey from a team he once played with.

His father cried as family gathered around to hug and console him.

Nyee remembers his nephew as sincere, loving and funny — a person who cared about everyone around him.

"The person walking into the hospital, he was good. He was healthy. He was telling them what's wrong with him and they turned him away," Nyee said.

"It brings the question: What do we do if you walk in (a hospital) and they kick you out? It's very deep and it's hurtful for us."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 30, 2022.

Mickey Djuric, The Canadian Press