KAWACATOOSE FIRST NATION — In the early 1970s, a few enterprising individuals from Kawacatoose First Nation embarked on a rather novel project − to record the community history and personal stories of their Elders.

Once the interviews were completed, the nearly 60 hours of recordings left the community and were virtually forgotten for half a century.

Except by Kawacatoose Elders like Bill Strongarm.

It was discovered, the reel-to-reel tapes were at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton, while the Provincial Archives of Alberta housed all the transcripts.

In 2020, Strongarm delivered a half-metre-tall stack of transcripts to Andrew Miller an associate professor at the First Nations University of Canada (FNUniv).

Miller learned the late Lawrence Tobacco from Kawacatoose was one of the individuals responsible for the recordings, while a man named Rick Yellowbird transcribed them. Incredibly, each recording contained detailed metadata such as the speaker, the topic, the interviewer, where the recording took place including the length of each interview.

“There’s fascinating history in these recordings,” said Miller who teaches Indigenous Studies. “Stories of things you often wouldn’t hear, like battles with the Blackfoot, histories of ceremonies being outlawed, stories of people being arrested.”

They also contain interesting concepts of the environment, human relationships and spirituality, he said.

Strongarm and Miller both knew the Cree recordings were infinitely valuable in terms of history and language preservation, but in 2020 a global pandemic had the world in sporadic lockdowns for much of the year.

In the latter part of 2021, FNUniv received some funding from the Library and Archives Canada’s Listen, Hear Our Voices initiative to begin the massive undertaking of processing valuable information.

Thus, was born the research and restoration project aptly named, These Stories Have Walked a Long Way.

Phase I of the project was to digitize and repatriate the recordings.

Miller spent three months going through the transcripts before compiling them into a 480-page Word document. The recordings were also digitized and professionally cleaned up.

On Oct. 31, it was announced, FNUniv was one of only 14 projects selected to receive further funding from Library and Archives Canada’s Listen, Hear our Voices initiative for Phase II of the project, which is to translate everything to English.

Miller says the Elders on the tapes were born in the early 1900s. Some of them shared stories from their Elders, which means this recorded history dates back decades and in some instances centuries.

“There are all manner of topics – they talk about the hungry times, they talk about the Blackfoot, they talk about hunting buffalo,” he said. “All of these things are really powerful.”

The title of the project, These Stories Have Walked a Long Way’ is taken directly from a recording from Elder Andrew Kay, who reflected on how many years the stories were passed down.

“Many of them are messages about living the good life,” said Miller. “This is their history, this is their ancestors who are speaking out of the past, sharing what their world and times are like in a very authentic way.”

The Elders working on the project noted the language used in the tapes was also very special.

“They’re all in Plains Cree, or what Elders today would call ‘High Cree’. It’s the equivalent to Shakespearean English,” said Miller. “A person can understand if it they grow accustomed to the ‘thous’ and ‘heretofore’. It’s a manner of speaking that’s no longer practised.”

There are nearly 60 hours of audio, and each hour takes about five to six hours to translate.

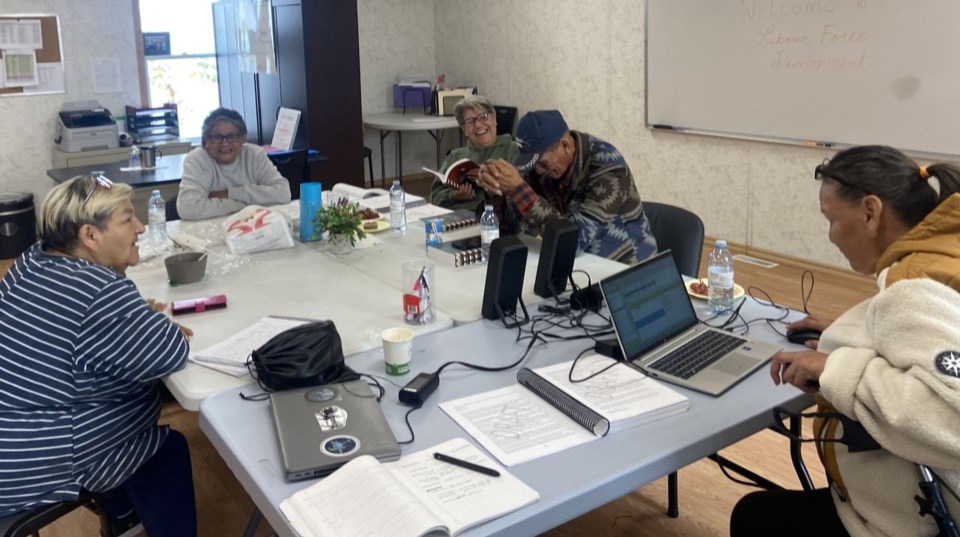

A team has been assembled to work on the translation process, including Strongarm, who also remembers when the recordings were made.

“I knew some of the speakers,” he said. “Some of them are my relatives, so it’s nice to hear them speak Cree. It gives you a sense of this sacred feeling. It makes you feel proud.”

Back then, Strongarm recalled asking the interviewees why they agreed to be recorded. He said some Elders had foresight to see the issues of the future.

“They said that our youth would forget our language, and this would help them get it back,” he said. “I think these (recordings) will revitalize our quest to learn.”

Strongarm enlisted Lawrence Tobacco’s children Caroline Poorman and Arnold Tobacco to help with translations.

“I walked in not knowing these recordings were the ones my dad did,” said Poorman. “When I heard my dad, it shocked me. I thought these stories were forgotten and were never coming back.”

Her father instilled in his children the importance of their Cree language and history.

“[He] would tell us how, we as native people, are related to all living things on earth,” said Poorman. “To me, I feel that there are young generations today that are lost. I think our children and grandchildren should know how connected we are, and how sacred our language is.”

She and her brother are amazed at the journey the recordings took before returning home.

“I think my father would be very proud and honoured that I’m translating what he recorded,” said Poorman. “He would be thankful that this language and these values are still alive.”

Miller, Strongarm, Poorman, and the rest of the team working on the translations currently have six hours completed and hope to have 10-20 done by the end of the year.

Miller, Strongarm, Poorman, and the rest of the team working on the translations currently have six completed and hope to have 10-20 done by the end of the year.