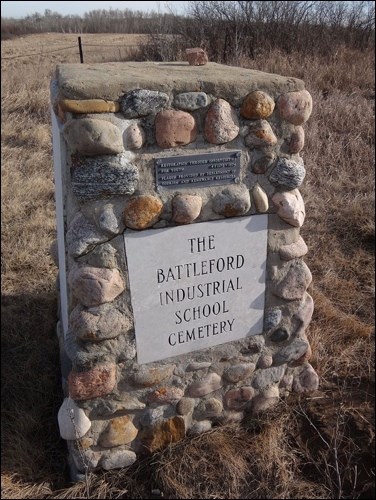

Efforts are under way towards commemorating a sometimes overlooked part of the Battlefords’ history: the Battleford Industrial School cemetery.

The cemetery is located on the grounds nearby the former location of Government House. The Battleford Industrial School was an Indian residential school located inside that building, which operated from 1883 to 1914.

At a presentation at the North Battleford Public Library on Wednesday night, lawyer Benedict Feist showed a slide presentation outlining the history of the residential school and the cemetery site.

It was a troubled history in many ways, representative of the “Indian policy” that was in place at the time in Canada. Illness, particularly tuberculosis, was a major problem at the school during those early days, as reported in accounts in the newspapers.

In 1974, archaeology students and staff from the University of Saskatchewan exhumed 72 graves from the site. A memorial was put up listing the names of all the students who could be identified.

One of those spearheading the commemoration project, local lawyer Eleanore Sunchild, said the goal is to “attempt to receive recognition of the cairn and the graveyard that’s behind the old Battleford Industrial residential school, and have it recognized as a cemetery – I would like it to be a historical site, so that it’s preserved and it can be used for educational purposes. There’s a lot of schools that want to see it because it is part of the whole history regarding residential schools and calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, so it is something that’s important to the community.”

The motivation to pursue an official designation for the cemetery, Feist said, came from the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, particularly in respect to missing children and unmarked burials.

The cemetery was mentioned directly in Vol. 4 of that report: “When the Battleford school closed in 1914, Principal E. Matheson reminded Indian Affairs that there was a school cemetery that contained the bodies of seventy to eighty individuals, most of whom were former students. He worried that unless the government took steps to care for the cemetery, it would be overrun by stray cattle. Matheson had good reason for wishing to see the cemetery maintained: several of his family members were buried there. These concerns proved prophetic, since the location of this cemetery is not recorded in the available historical documentation, and neither does it appear in an internet search of Battleford cemeteries.

Feist pointed to that passage of the report and also noted the difficulties people had in locating the cemetery.

“It’s something, I think, we’re called upon in the Battlefords to do something about,” said Feist at the meeting.

But the challenges go beyond simply locating the cemetery on a map. Accessing the site is also an issue.

The land that the cemetery is located on is in private hands in the RM of Battle River and therefore cannot be easily accessed by those interested in seeing it, including school groups.

Members of the Battlefords North West Historical Society have been able to access the cemetery on an annual basis to do some general upkeep there. Several members of the Historical Society were on hand at the public meeting, where they expressed their interest in the historical value of the site.

There are a number of items proponents of the cemetery commemoration project are seeking.

Among them is heritage status from the municipal, federal and provincial governments for permanent protection of the site. They also want regular access to the site including a road or a wheelchair/Elder accessible paved path, along with signs from the highway.

They also want to see public and highly visible monuments placed at the site, following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls to action. The intention is for this effort to be led by Indigenous people and local First Nation communities.

There are some other initiatives the group wants to pursue, including adding to the Internet records about the cemetery on Facebook and Wikimedia Commons.

A big item would be dealing with the issue of the land. What the proponents would like to do is take over ownership of the portion of the private land where the cemetery is located, either through a subdivision and/or land purchase, with the Federation of Sovereign Indigeneous Nations or another group taking on ownership.

“I think we need to enter into some sort of discussion with the landowner about how we can achieve having that site preserved as a cemetery or historical site,” said Sunchild. “We’ve talked about some options tonight and we need to explore those further.”

Sunchild noted the importance of recognizing the legacy of Indian residential schools.

“It’s very important because we all suffer the effects of Indian residential schools, whether we are native or non-native,” she said. “We deal with the intergenerational effects in our society. We see it in this community, I think there is a divide between our people, and a lot of that stems from the schools.”

The next steps for those backing the project is to hold another meeting as a group to discuss further how to achieve their goals. They also are seeking to do more research of the site and work with the Historical Society as well.