With a cup of coffee in hand, I was recently reading through a major wholesale perennial catalogue that serves Canada’s prairies, and becoming increasingly dismayed at the hardiness zones into which they had placed some of my favourite plants. Daylilies in zone 3? Peonies in zone 3? Hadn’t I been growing these for decades in zone 2? What was with these guys? Didn’t they know anything?

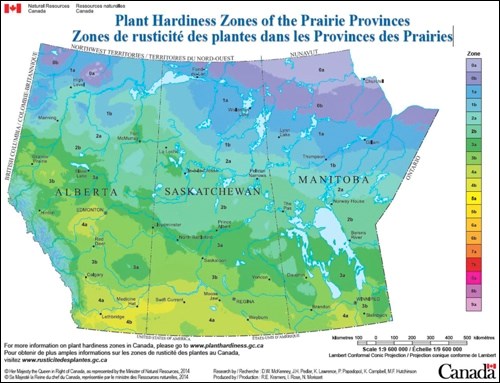

When I came to the last page, it dawned on me. Yes, indeed. In full colour, there was a map of Canada. Their catalogue designations were based on the new Canadian hardiness zone map.

Oh, my gosh! I will have to relearn everything that had become second nature. Saskatoon is now in zone 3b. How I loved the old designation! I had delighted, as do many prairie people, of bragging that I garden (the implication is, of course, of successfully gardening) in zone 2b. I would quote Hamlet, “To be or not to be, that is the question,” and hope whoever was listening would get the literary and horticultural allusions. Change will not come easily.

Along with Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Steinbach and Brandon, Man., Regina and Red Deer, Alta. are now in zone 3b. Prince Albert, the Battlefords and Lloydminster are in zone 3a. Weyburn, Swift Current, and Calgary, Alta. are in zone 4a. And my much coveted zone 2b includes The Pas, Man., La Ronge and Ile-a-la-Crosse.

Why a new plant hardiness map? Part of the reason lies with climate change. Incrementally, we’re getting warmer. The original version was developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in 1967. Hardiness zones were based on seven factors: average temperature in the coldest month, average temperature of the warmest month; length of frost-free period; total rainfall from June to November; a winter factor; average maximum snow depth and maximum wind gust. This first map used climate norms from 1930-60. The map was updated once before by simply using updated climate norms (1961-90). The most recent version, updated by Natural Resources Canada, also uses more recent climate norms (1981-2010), but it also takes into account the effects of elevation and uses modern analytical and mapping technologies.

American seed catalogues will usually reference the USDA hardiness zone map. The USDA map is based simply on extreme minimum winter temperature over the last 30 years. And while both the USDA and the Canadian systems use the same number-letter system to name zones, similarly named zones are not necessarily equivalent (see http://planthardiness.gc.ca for more information; interactive maps are available to determine your zone in both the Canadian and USDA systems).

Some emotions are (as they say) hardwired. In my heart, I will always garden in zone 2b. But I will have to get my head around this new map and go with the reality of climate change and the new plant hardiness designations. To further complicate the issue, as gardeners we should keep in mind that many of the zone designations in plant catalogs and on labels on plants and in pots at garden centres and nurseries may lag behind the new map for several years.

We can (and inevitably will) continue to “push the zones” and try to include new, different, and “tender” trees, shrubs and perennials in our landscapes, but with a slightly altered zonation reality.

Sara is the author of numerous gardening books, among them the revised Creating the Prairie Xeriscape. And with Hugh Skinner: Gardening Naturally; Trees and Shrubs for the Prairies, and Groundcovers & Vines for the Prairies. Expect Fruit for Northern Gardens with Bob Bors in November, 2017.

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (www.saskperennial.ca; [email protected]; www.facebook.com/saskperennial). Check out our Bulletin Board or Calendar for upcoming garden information sessions, workshops, tours and other events.