Arcola's Adrian Paton is a renowned plains and prairie historian, photographic curator and writer. His collection of photographs depicting Saskatchewan's early history is the subject of a travelling exhibit which is currently on display in museums and libraries throughout the province, and which also makes up a curriculum package aimed at students from grades three to five.

Paton's passion for history was ignited when he was 10-years-old.

“I got a photo album for Christmas and my mom had some negatives. Every time I'd have a few coins, I'd go to town with a negative or two and get the pictures developed.”

“Later, my grandmother died at the age of 105 and my dad inherited a box of old pictures,” adds Paton. “I spent a few days with my mother and my dad packaging them up and some I kept, because they were historic.”

Paton- a native of Gravelbourg- came to Arcola with his family to farm- and his adopted hometown is the place where his interest in plains and prairie history took root.

“About 25 years ago, we worked on a history book project for the Arcola-Kisbey area,” he says. “That's when I learned about a photographer- D.M. Buchanan of Arcola. He was definitely an innovator. He not only took photographs of babies, weddings and funerals- he took a lot of farm scenes, too.”

“Just as we were finishing the history book, a local lady brought in a very good picture of a ploughing scene and that really got me interested in seeing more of Buchanan's work.”

However, Paton's search for more of Buchanan's photographs was tinged with both success and disappointment.

“In one case, boxes of his negatives had been taken to the dump,” he says. “But another gentleman had a box of 62 glass negatives. They were perfectly good, but dirty. I dusted them off with a cloth with the bare minimum of moisture so they wouldn't flake and I managed to get most- but not all- of the dust off.”

“A good percentage of the people in the pictures are from Arcola,” adds Paton. “But a lot of the glass negatives were lost, because during the Great Depression in the 1930s, people used glass negatives in barn windows.”

“But discovering Buchanan's work- that's when I really got serious.”

Paton's collection is meticulously catalogued in binders and 800 of his nearly 8,000 images have been digitized. That job was completed over two summers by two history students from the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon.

Paton stresses that he is not a collector of objects and artifacts, but rather a keeper of history who aims to impart his knowledge to others.

At the official launch of Paton's exhibit in Arcola, Keith Carlson of the Saskatchewan History and Folklore Society told The Observer: “We asked him what he wanted to see done with his collection and Adrian, being a generous man, simply said he wanted people to see them and share them,” adding “It's a fantastic collection.”

Paton's generosity means that he fields requests from academics, members of the media (most recently, he's been interviewed by CBC Radio) and people who want to entrust aspects of their families' histories with him.

“A paper interviewed me and I received a call shortly after at 9:30 at night,” says Paton. “An elderly woman told me 'We're destined to meet.'”

“It turned out that she was the niece of a man called H. Pittman of Wauchope. He lived near Redvers on a farm, but he was also a botanist and a photographer. He was to that community what D. W. Buchanan was to Arcola.”

“She had boxes of her uncle's negatives and many of his pictures were of farming families from the area and of farm life.”

“Some of the first photographs in my collection were made in southern Saskatchwan,” he says. “For example, I've got a whole section on sod houses.”

“Of course, when you're talking about prairie history, everyone writes about the Dirty Thirties,” says Paton. “But individual stories are sometimes surprising.”

“I asked one elderly lady if she could live one part of her life over, what would it be? She told me that the Great Depression would be the period she would choose.”

“That surprised me and I asked her 'Why?' and she said that the cameraderie was the reason. She said everybody was broke and her family had no money, either. But people were all in the same boat and helped each other out.”

“She was a local lady and she said because her husband was a hunter and they lived on the edge of the Moose Mountains, they always had food.”

However, Paton's interest in Saskatchewan history isn't confined to the province's settlers.

“My collection and area of interest has grown to encompass the Great Plains area of North America- and right now, I'm working on a (non-fiction) book about the true story of two tribes and a battle between them.”

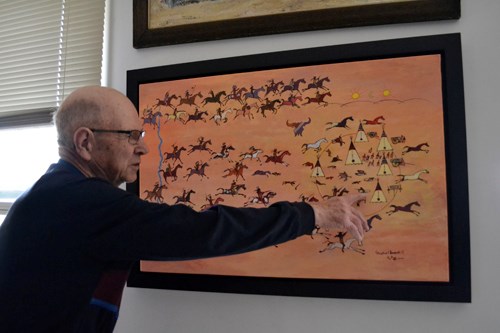

“I've commissioned a painting by Michael Lonechild that depicts the story for the book,” he adds. “Two tribes- the Pasquas-which means 'prairie'- from the Qu'Appelles and their friends the Mandans on the Missouri River.”

“The Pasquas wanted to visit their friends and they couldn't get permission to go from the Indian agent, so they took off and the story starts from there.”

Paton says the story is a sad one- a real-life battle between friends sparked by the theft of a horse and a killing.

“It was often like a game to take a horse,” he explains. “But in this case, it turned into a more serious and tragic story.”

Paton says that First Nations people and cultures suffered injustices and as a result, many of their beliefs and traditions are not widely known.

“For example, women had a lot of power and respect within the tribe,” he says. “They did a lot of the work while the men were off hunting. Women owned the teepees and all of the belongings in them. They had a say in anything inportant and they had control of the girls until they married and control of the boys until their voices changed.”

For Paton, history is eternal and alive.

“I farmed five miles south of Arcola,” he says. “One hill on the land is called Hawk Hill. Michael Lonechild has painted it and it's the highest point between the Souris River and the Moose Mountains.”

“Once, I was out there and I found a 6,000-year-old arrowhead,” he says. “I'm not someone who collects things. For me, seeing that arrowhead made we wish that for one day, I could see that land as it was when the Native people lived there.”

“I'm really interested in a wide spectrum of prairie life and that includes everyone's stories.”