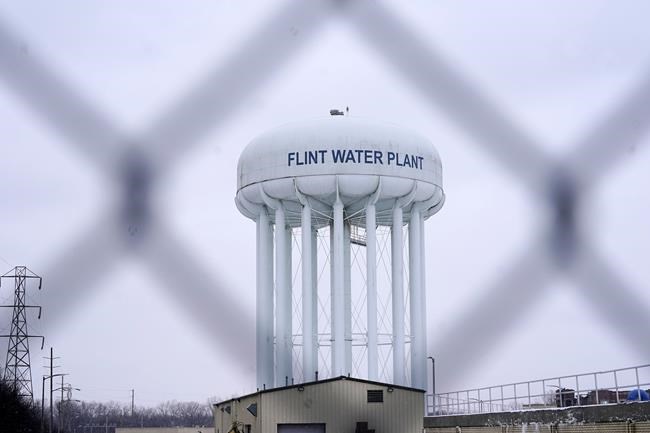

DETROIT (AP) — A judge declared a mistrial Thursday after jurors said they couldn't reach a unanimous verdict in a dispute over whether two engineering firms should bear some responsibility for Flint's lead-contaminated water.

Veolia North America and Lockwood, Andrews & Newman, known as LAN, were accused of not doing enough to get Flint to treat the highly corrosive water or to urge a return to a regional water supplier.

The eight-person jury met for roughly seven days after hearing evidence for months. The jury first signaled on July 28 that it couldn't reach a verdict before taking a planned 11-day break. The group returned to work Tuesday.

“Further deliberations will only result in stress and anxiety with no unanimous decision without someone having to surrender their honest convictions, solely for the purpose of returning a verdict,” the jury said in a new note Thursday.

U.S. Magistrate Judge David Grand declared a mistrial, rejecting a request by lawyers for four children to allow a verdict that's less than unanimous.

“This is not a focus group,” Grand said.

The trial centered on the engineering firms and the effects of lead on the children, not all Flint residents. But the result was being closely watched because there are other cases pending against Veolia and LAN.

The firms were not part of a landmark $626 million deal involving property owners, thousands of residents of the majority-Black city, the state of Michigan and other parties.

“We don't see this as a defeat,” Veolia attorney Dan Stein told The Associated Press. “The plaintiffs were the ones trying to prove their claims to the jury, and they were unable to do so.”

Corey Stern, an attorney for the children, said he was only one juror shy from winning the case. The lack of a verdict means a trial can be held again with a different jury.

“I'm fired up for the next one,” Stern said. “I wish the judge would schedule it for Monday. I hated leaving the courthouse. You’re an inch from the goal line after toting the ball for 99 yards.”

Flint's water became contaminated in 2014-15 because water pulled from the Flint River wasn’t treated to reduce the corrosive effect on lead pipes. Citing cost, managers appointed by then-Gov. Rick Snyder stopped using water from a Detroit agency and switched to the river while awaiting a new pipeline to Lake Huron.

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission said the bad water was the result of systemic racism in the city, doubting that the water switch and the spurning of complaints would have occurred in a white, prosperous community.

During closing arguments, attorneys for the children argued that Veolia should be held 50% responsible for lead contamination and that LAN should be held 25% responsible, with public officials making up the balance.

But Veolia's lawyers noted the firm was briefly hired in the middle of the crisis, not before the spigot was turned on. LAN said an engineer repeatedly recommended that Flint test the river water for weeks to determine what treatments would be necessary.

LAN attorney Wayne Mason said outside engineers were getting lumped in with a “platoon of bad actors,” namely state and local officials who controlled all major decisions about the water. The health effects on the four children were also challenged at trial.

Snyder was summoned as a witness but declined to answer questions, citing his right against self-incrimination.

He was indicted on misdemeanor charges in a separate Flint water investigation. The Michigan Supreme Court said the indictment was invalid, though state prosecutors are trying to reinstate the charges.

The jury instead watched a video of Snyder’s 2020 interview with lawyers.

“I wish this never would have happened,” he said of the water mess, acknowledging mistakes by government.

___

Follow Ed White at http://twitter.com/edwritez

Ed White, The Associated Press