Rural Saskatchewan may not seem the most likely place to find an internationally recognized expert on wolves, but Dr. Paul Paquet feels right at home.

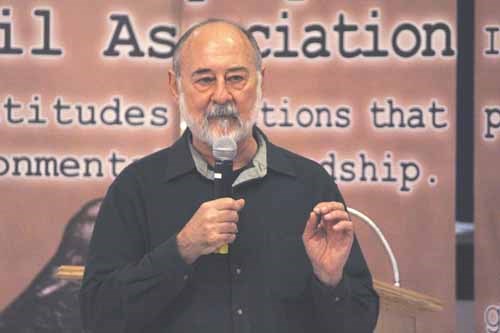

Paquet, an adjunct professor at the U of S College of Veterinary Medicine with faculty postings at half a dozen other Canadian universities, was among the guest speakers at the Yellowhead Flyway Birding Trail Association Annual Symposium in Saltcoats on the weekend.

The researcher spends part of each year studying the coastal wolves of BC and Alaska - his most recent project in more than 35 years of study into wolf populations around the world - but the place he calls home is Meacham, SK.

In 35 years, Paquet has seen the landscape of North American wolf conservation change dramatically.

"Wolves have gone through a period when they were really suppressed in terms of their geographic distribution and numbers, and then have started to recover over the years, generally with the cessation of the persecution that was occurring," he says.

But with that change has come a push from the other direction. As wolves creep back into areas from which they have been absent for decades, the old prejudices against them have returned as well.

"People are less receptive to wolves, and there are huge efforts to control them that are not dissimilar to what was occurring in the 1950s and the early 1900s, and so on."

Such attitudes are unjustified, argues Paquet. The animal's reputation as a killer of humans, for example, is largely fantasy. Moose are responsible for far more human injuries and deaths in North America; wolves, by comparison, are extraordinarily safe considering their range and abilities.

Wolves also frequently receive unfair blame for killing livestock, Paquet adds. While wolves and coyotes are known to prey on livestock, most reported instances of livestock predation are actually cases where the animals died of other causes and were later picked at by scavengers.

Centuries of persecution against wolves have already taken a permanent toll. The gray wolf, thought to have been at one time the most genetically diverse species in history, has lost half its diversity in North America forever.

Paquet worries that this loss has weakened the wolf's chances of successfully adapting to a future that will "definitely not look like the present."

Humans remain the greatest threat to wolf populations. Forestry, oil & gas development, mining, road & infrastructure construction: all of these can wreak havoc on habitats, and while wolves might survive one or two of them in isolation, the combination of several can be catastrophic.

Paquet is not optimistic that the necessary steps toward preservation and conservation of nature will be taken. As long as human populations continue to grow without restraint, species such as wolves that depend on the same resources will inevitably dwindle.

"In ecology, we call it competitive exclusion," says Paquet.

Humans have the intelligence to overcome this natural law, but only with sufficient willpower and solid information on which to base decisions.

That's why it's so troubling, says Paquet, that no research into large carnivores is being done in Saskatchewan.

"The information we have is largely anecdotal. We just plow ahead and make a lot of assumptions that may not be warranted, and that's a really dangerous way to go."