When you play a lot of board games you learn that some are outstanding – say crokinole – some are a deeply flawed waste of time – think Monopoly – and some are games which remain something of a mystery.

The games that are a mystery are the ones that you have heard and/or read good things about, you sit down and play the game and the expected pizazz is simply not there.

Regular readers will be aware that this writer has a soft spot for abstract strategy games. I like the challenge of competition without the influence of an unlucky dice roll, or draw of a card.

I also tend to appreciate vintage games a lot. If a board game is still being played decades after its creation, especially in an era dominated by video games it has to have something going for it.

Which brings us to the game of Hex.

Hex was invented by the Danish mathematician and poet Piet Hein, who introduced the game in 1942 at the Niels Bohr Institute, according to www.boardgamegeek.com. “The same year Hex appeared in the Danish newspaper Politiken under the name Polygon. Hein introduced the game to the readers on December 26, 1942 and during the following four months gave them a problem each day to begin with - eventually two days a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The solution would always appear in the following column.”

Interesting the game “was independently invented by mathematician John Nash in 1947 at Princeton University.”

In 1952, Parker Brothers marketed a version. They called their version Hex, and the name stuck. As a side note the ‘collector’ in me would love to happen upon the Parker Brothers version at a yard sale one day.

Now some of the best games have limited rules. If a game can offer a compelling experience without pages of rules to learn and follow it is simply a huge bonus.

In that regard Hex is a standout.

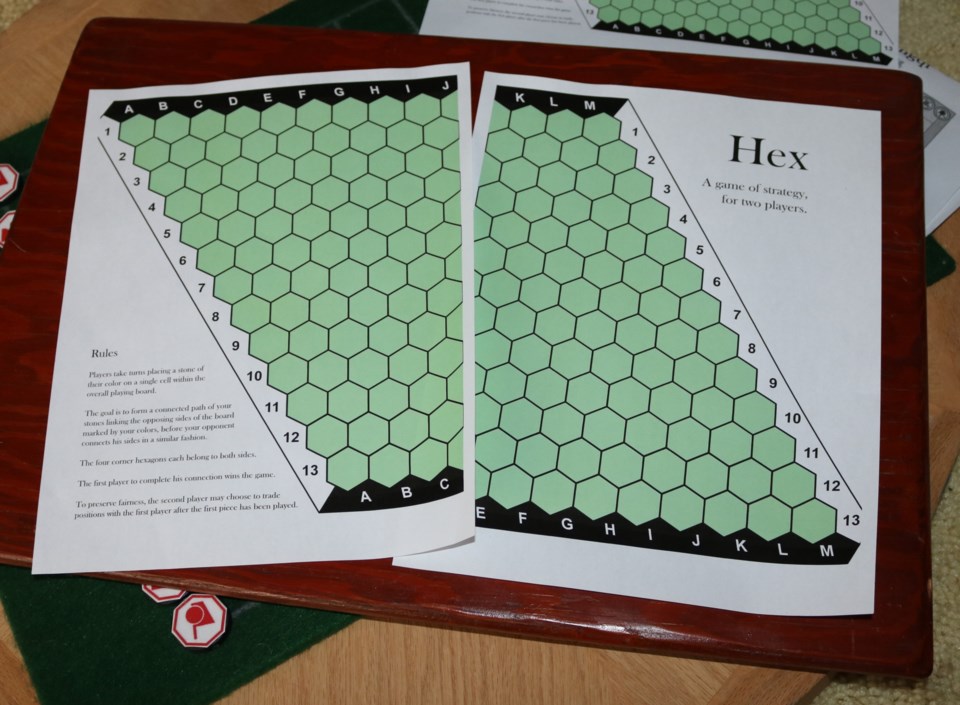

It is traditionally played on an 11×11 rhombus board, although 13×13 and 19×19 boards are also popular.

“Each player is assigned a pair of opposite sides of the board which they must try to connect by taking turns placing a stone of their colour onto any empty space,” explains Wikipedia. “Once placed, the stones are unable to be moved or removed. A player wins when they successfully connect their sides together through a chain of adjacent stones.”

Draws are impossible in Hex due to the topology of the game board.

Since the first player to move in Hex has a distinct advantage, the pie rule is generally implemented for fairness. This rule allows the second player to choose whether to switch positions with the first player after the first player makes the first move.

It is the first player advantage that is quite noticeable in Hex that perhaps dulls the experience for me. A game is ultimately a race to see which player completes a chain first, and that first piece on the board is a big advantage in a race.

Yes, there are ways to block chains, although the risk is the blockade fails and the game is lost.

It is likely, that is the case with some games, that full appreciation of Hex comes with greater experience. Players veer from the pure race across the board and begin setting patterns that can block or connect later in a game.

So I have printed a board and undertaken to lay it on a nice wooden board found ages ago at a yard sale, ready to give Hex a bit more of a chance to ‘Wow’ me – time of course will tell.

For those wanting a board head to www.boardgamegeek.com where there are several choices to print. Go stones, or coloured glass beads is all your need in terms of play pieces.

There are also a number of resources for Hex on the internet, including several real-time servers, a search will find.

For those wanting a board head to www.boardgamegeek.com where there are several choices to print. Go stones, or coloured glass beads is all your need in terms of play pieces.

There are also a number of resources for Hex on the internet, including several real-time servers, a search will find.

.