If you think COVID-19 was suddenly in the news a lot over the summer, you’re probably right.

Throughout August, outlets in both Canada and the United States ran headlines about high COVID levels, the summer surge of cases, timing of booster shots and reviving the use of face masks.

As numerous athletes tested positive for COVID at the Olympics in Paris, news outlets reminded Canadians that COVID is still a threat, and that summer cold symptoms might in fact be COVID.

The list of COVID news stories could go on and on, but what many experts seem to agree on is that this surge is a pretty big deal. In fact, Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health predicts this wave might be the biggest summer surge since the virus started, according to an article in CNN.

Why COVID is surging now?

But why is the biggest surge occurring now, after health experts declared the end of the global health emergency over a year ago?

My research team at Royal Roads University studied how to share evidence-based health information during the COVID-19 pandemic, collecting interview, survey and experimental data between 2020 and 2023. We developed a framework that employed the health belief model for understanding why people may choose to act on health promoting behaviours — like adopting masks and vaccines during a pandemic.

Looking at the news about this latest surge, I think the health belief model can help people understand why our biggest summer surge has specifically occurred after the pandemic stage of the virus has been declared long over.

The health belief model

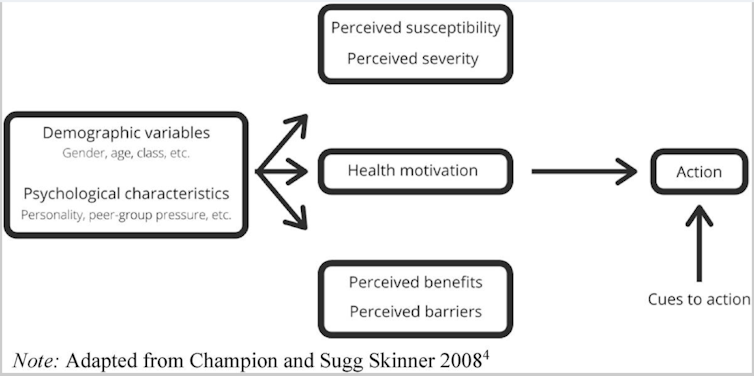

The health belief model helps public health practitioners and doctors understand what motivates people to adopt a positive health action (like quitting smoking or exercising), or act to reduce exposure to a negative health event (like getting a flu vaccine or practising safer sex).

This model tells us that the likelihood of a person taking action towards a particular health outcome depends on the person’s perception of the risk of the negative health outcome to themselves personally, and also their perception of the benefit of the risk reducing behaviour. People also need to feel like they have the ability to take the necessary action, and that the action will be effective.

A summary of the health belief model can be seen in a diagram.

Adopting the health belief model in practice means that public health communicators and the media need to illuminate both the risk of the negative health outcome, and the benefits and effectiveness of the risk reducing behaviours that will help people avoid the health danger. Both of these elements have been lacking since the end of the global emergency declaration for COVID-19.

Health belief and the summer of COVID

The reason I think we’re seeing such a surge now is because people don’t believe COVID is a risk, and they also don’t understand how getting vaccinations beyond the initial vaccine series from a few years ago would protect them now.

When public health officials communicated the end to the global emergency stage of COVID, they unwittingly gave the public the impression that the danger was over. This decreased perceived risk and, with it, the likelihood that people would engage in regular vaccination, mask wearing and hand washing.

Furthermore, Health Canada no longer keeps or reports the latest COVID numbers, which means that many people have no real idea of the relative risk to themselves for gathering in public spaces, making them less likely to take precautions and more likely to pass on the virus.

Reporting on COVID in the media has not helped matters. While the dangers of new variants began to be reported as early as May of this year, the reporting on the spread of the virus didn’t really start to pick up until Olympians started collapsing after events.

This is the biggest summer wave because people are under-vaccinated and have stopped taking other precautions like distancing or wearing masks. And the reasons why we’re not taking these important risk-reduction behaviours is because many of us believe that COVID is over, or, if not over, that it’s not a big deal.

But long COVID is still a risk and as of mid-August, the Public Health Agency of Canada reported over four million COVID cases in Canada. It’s not “just the flu” either, as with this summer surge, the World Health Organization also reports increases in hospitalizations.

COVID is not the emergency it once was, but it’s still a health threat, and we’d be wise to reduce our risk of getting it. That’s why public health communicators should re-integrate strategies that employ the health belief model to remind people that they are at risk, they can do something to reduce that risk and they will be better off for it.![]()

Jaigris Hodson, Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, Royal Roads University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The commentaries offered on SaskToday.ca are intended to provide thought-provoking material for our readers. The opinions expressed are those of the authors. Contributors' articles or letters do not necessarily reflect the opinion of any SaskToday.ca staff.